Understanding Charles Lindbergh

May 20, 2025

By Bob van der Linden

On May 20–21, 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh piloted his Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis on the first solo, nonstop flight across the Atlantic. The former air mail pilot and barnstormer flew from New York to Paris in 33 and a half hours, a distance of about 5,800 kilometers (3,610 miles). A crowd of 150,000 greeted him when he landed at Le Bourget Airport.

By flying directly over the Atlantic Ocean from one large city to another, Lindbergh demonstrated in a spectacular and personal way different from other long-distance flights that vast distances were no longer barriers and that the potential for long-distance air travel was quickly becoming a reality. When Lindbergh landed in Paris, the American public became enamored with him and with aviation. This stunning achievement produced the “Lindbergh boom”—aircraft industry stocks rose in value and interest in commercial aviation skyrocketed in the United States.

The air age had arrived.

Lindbergh’s Newfound Fame

Overnight, Lindbergh became a modern international celebrity who was preyed upon by the media. Immense crowds welcomed him in Europe, the United States, and Latin America. Fame engulfed him. His image and that of his aircraft appeared on almost every type of consumer object imaginable. His celebrity endured, but at great personal cost, while his social and political beliefs turned him into a polarizing figure.

These commemorative cufflinks in the Museum’s collection are one example of the many types of consumer products created to commemorate Lindbergh’s flight.

Lindbergh used his newly found fame to promote commercial aviation. After his transatlantic flight, he embarked on a goodwill tour, flying around the United States and Latin America speaking about the future of commercial air travel.

He accepted a position as technical advisor for Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT). As technical advisor, he established the airline’s routes, organized its infrastructure, and selected its equipment. TAT merged with parts of Western Air Express to become Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) in 1930.

Lindbergh also served as a member of the board of directors for Pan American Airways for the rest of his life and was a key player in that airline’s expansion. He and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh flew on two important survey flights on behalf of Pan Am, pioneering potential commercial routes across the Pacific Ocean in 1931 and the Atlantic in 1933 in their Lockheed Sirius floatplane. These flights helped Pan Am become the first airline to open commercial service across both oceans.

The Kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr.

Lindbergh was arguably the most famous man in the world in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He became wealthy from his aviation investments and the publication of his book We. His wife, Anne, was the daughter of Dwight Morrow who was the partner of financier J.P. Morgan, the massively wealthy creator of the huge U.S. Steel Corporation among many other business accomplishments. The Lindberghs’ Pan Am survey flights made Anne a public figure as well. Because of their fame and wealth, the Lindberghs were an obvious target for extortion and kidnapping threats.

On the evening of March 1, 1932, the Lindberghs’ 20-month-old baby Charles Jr. was taken from his nursery through a second story window at their home in Hopewell, New Jersey. The news of the child’s kidnapping stunned the nation, creating another media frenzy. The crisis turned to heartbreak in May when the child’s lifeless body was discovered nearby. More lurid press coverage followed the arrest, trial, and execution of Bruno Richard Hauptmann in 1936 for the crime.

Lindbergh was always intensely private about his personal life. He internalized his profound grief over the murder of his son. He blamed the media for the circus that surrounded him, and he blamed them for encouraging the kidnappers. Lindbergh forever hated the press. He became disenchanted with living in the U.S., the constant harassment, and especially the death threats against his second son Jon. The Lindberghs moved to Britain, and later France, not long after Hauptmann’s trial.

A Complicated Relationship with Pre-World War II Germany

While safely in Europe during the mid-1930s, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh were drawn to the appearance of law and order in pre-World War II Germany—understandable, perhaps, in response to the kidnapping and murder of their son that had driven them to Europe in the first place.

During his time in Europe, Lindbergh visited Germany several times and explored its developing aviation industry at the request of Maj. Truman Smith, the U.S. military attaché to Germany. Lindbergh, who was a Colonel in the Army reserves, reported what he learned in great detail to the U.S. Army Air Corps. That information was put to good use by the U.S. military.

Lindbergh’s tours of Germany were well-orchestrated by the Luftwaffe leadership who wished to influence his opinion. It could therefore be argued that Lindbergh was a useful tool of the Germans at this point, because he recommended that the U.S. not get involved in a future European war due to his impression of the Luftwaffe’s power.

In October 1938, Herman Goering presented Lindbergh the Service Cross of the German Eagle (with Star) on behalf of Germany and its leader Adolf Hitler. This award was for Lindbergh’s historic 1927 transatlantic flight and his contributions to aviation.

Herman Goering presents Lindbergh with the Service Cross of the German Eagle (with Star).

Lindbergh saw nothing wrong with accepting a medal from a head of state and could not understand why he was pressured to return it. However, this occurred only weeks after the Munich Crisis, when Germany seized the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, and only a month before the infamous “Kristallnacht” pogrom against German Jewish citizens. Lindbergh was blind to the negative appearance of accepting the award to those who opposed Hitler and Germany, but that was very much in keeping with his personality. He felt that returning the medal would be an insult to the German leadership and might provoke a diplomatic incident. Regardless, Lindbergh could not admit a mistake.

Lindbergh and the America First Movement

The Lindbergh family returned to the United States in 1939. Lindbergh used his fame to become the spokesman for the America First Committee in the late 1930s, which worked to keep the U.S. out of the brewing conflict in Europe. Many of Lindbergh’s political beliefs were shaped by his father and his upbringing in the Midwest.

Lindbergh was the son of a Progressive Republican congressman from Minnesota. His father, Charles August Lindbergh possessed Populist agrarian views prevalent in the Midwest and adamantly opposed the so-called “Money Trust,” an alleged de facto monopoly of powerful New York bankers, led by J.P. Morgan. The farmers the senior Lindbergh represented were wary of more cosmopolitan Americans, especially bankers from the east coast. They assumed bankers were to blame for the travails of Midwestern farmers and incorrectly assumed they were primarily Jewish. Many of Lindbergh Sr.’s constituents were xenophobic and often antisemitic. These were not uncommon themes throughout the country at the time.

Lindbergh Sr. was also adamantly isolationist in his politics, wishing to avoid any involvement with international affairs and in particular, international conflicts. He was one of the few Representatives to vote against America’s entry into World War I in 1917.

Lindbergh accepted his father’s beliefs and was very outspoken about them. In a now-infamous September 1941 speech in Des Moines, Iowa, Lindbergh blamed Britain, France, and, without any evidence, unnamed people of the Jewish faith for international tensions. He did not blame Germany. This was too much for most people to tolerate. With the coming of the war for the U.S. only three months later, Lindbergh’s credibility with a large portion of the nation was destroyed.

Antisemitism and Interest in Eugenics

Despite accusations to the contrary, Lindbergh was not a Nazi. But he was antisemitic, although he did not understand that he was. Lindbergh toured Germany after the war, including a visit to the Nordhausen concentration camp, and he was left shaken and appalled by the Nazis’ debasement of humanity. He condemned the horrors of Nazism in the strongest terms and adamantly supported the Nurenburg war trials. But earlier, he also expressed an interest in eugenics – the study of selective reproduction to enhance the genetic characteristics of a human population–so-called “racial purity.” Eugenics was a popular 19th century theory in the Western world that was embraced by the Nazi Party, among others.

When he lived in France in the 1930s, Lindbergh met and shared values with Dr. Alexis Carrel, the winner of the 1912 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. They worked together to develop the perfusion pump, which was an important step that would lead to open-heart surgery and organ transplants. Carrell was also a strong advocate of eugenics. Carrell later worked with the Vichy French government and was later accused of collaboration with Germany after the Liberation of France. In the words of Lindbergh’s biographer, A. Scott Berg, “[Carrel] and Lindbergh carried on such a discussion … delving into the subject of ‘Race betterment.’ Unfortunately, similar discussions were raging through the Third Reich, a coincidence that would not be lost on future detractors of either Carrel or Lindbergh.”

Why is There a Swastika on the Spirit of St. Louis Propeller Spinner?

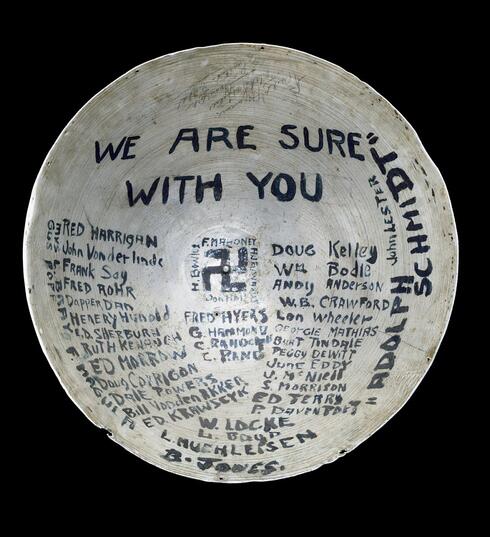

Because of Lindbergh’s history of antisemitism, many Museum visitors have asked if the swastika painted inside the propeller spinner of the Spirit of St. Louis is proof of Lindbergh’s Nazi sympathies. However, that swastika comes from an entirely different context unaffiliated with the Nazi Party.

The history of the swastika goes back centuries. The symbol was present in numerous cultures long before it was usurped by Hitler and his racist National Socialist, or Nazi, movement in Germany. Indeed, the swastika was widely used by aviators in the United States and Europe as a good luck symbol long before Hitler rose to power. For instance, it is present in the Sioux Native American headdress used as the logo for the famous Lafayette Escadrille, the French fighter squadron composed of American volunteers during World War I, years before the creation of the Nazi party.

When Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic in 1927, the National Socialist party was a small political entity. Mainline political parties in Germany dismissed them as extreme right eccentrics and mistakenly did not see Nazis as a threat. In 1927, the National Socialist party received only 2.6 percent of the vote for the German federal election. They rose to prominence and international attention only after the coming of the Great Depression in 1929. The Depression brought massive unemployment and a population looking for scapegoats for their dire situation. When Lindbergh made his 1927 flight and the swastika symbol was painted on the propeller spinner, the horrors of what the Nazis were to become were, as yet, unknown. They would not be revealed until the mid-1930s.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh was an obscure 25-year-old air mail pilot from Minnesota. It is highly unlikely that Lindbergh or the people at Ryan Airlines who built the Spirit of St. Louis had any knowledge of Nazis. Instead, the workers expressed their solidarity with him through their comment that “We are With You.” They wished Lindbergh a safe flight through the incorporation of what was then an apolitical good luck symbol, popular with aviators in the U.S. – a swastika. It meant nothing more to them. The workers, not Lindbergh, painted the symbol inside the spinner cap.

How Lindbergh Supported the Allies in World War II

Lindbergh strongly disagreed with President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) about any U.S. intervention into the developing conflict in Europe in the late 1930s but remained a strong believer in democracy. In April 1941, Lindbergh resigned his commission as a Colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve in protest of FDR’s interventionist policies.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States directly into World War II, Lindbergh felt it was his duty as a citizen to fight. He appealed to FDR for his reinstatement but was denied. Roosevelt remained bitter about Lindbergh’s vocal isolationism and a personal feud they had that dated back to the Air Mail Crisis of 1934, when Lindbergh had publicly called out FDR for canceling the air mail contracts.

Lindbergh contributed to the war effort as an advisor to the Ford Motor Company and as a technical advisor for the United Aircraft Corporation. He toured the south Pacific helping U.S. pilots extend the range and payload of their Vought F4U Corsairs and Lockheed P-38 Lightnings. In fact, he showed them how to double the range of the P-38 using different engine management techniques that he learned when flying his Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic years earlier. He actually flew many combat missions, despite being a civilian, and was able to shoot down a Japanese aircraft.

After World War II, Lindbergh Remained Active in Aviation

After the Second World War, Lindbergh’s strong anti-Communist stance and the publication of his book The Spirit of St. Louis and subsequent movie helped to rehabilitate his reputation. He continued his work with Pan American World Airways. He helped them expand their routes around the world and inaugurate the Jet Age in commercial air transportation. He began to question the effects of technology and science on society in light of the terrible destruction wrought by the sophisticated instruments of war. He also developed an active interest in environmentalism and conservation.

During this time, Lindbergh also grew more distant from his wife, though they stayed together until his death from cancer in August 1974. When Anne passed away in 2001, the world was shocked to learn that Charles had fathered seven children with three German women, two of whom were sisters and the third of whom was his private secretary in Europe during his many trips to Europe between 1958 and 1967.

Fifty years after his death, and nearly 100 since he was thrust into the global spotlight, Charles Lindbergh’s legacy remains complicated. As one of the most famous pilots to ever live, he looms large over the history of flight. His impact on aviation cannot be overstated, but we must also acknowledge his social and political beliefs and the way they shaped his life. To fully understand the legacy of one of America’s most celebrated and controversial heroes, we must look at the span of his life head-on.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.